Standard Polish (Indo-European)

Polish is not discussed in the paper. While the language is related to Russian, it raises some very different issues. Just as in Russian, clear arguments in favor of complex segments are difficult to make on phonotactic grounds alone: both languages allow many combinations of stops and fricatives. But some of Trubetzkoy's other arguments, which fail for Russian, actually make sense for Polish. For one, Polish has a more symmetrical inventory of affricates: wherever there are contrastive strident fricatives, there are also voiced and voiceless affricates. Russian, on the other hand, has a gapped inventory with respect to voicing (all phonemic affricates are voiceless), as well as place (there is no retroflex affricate).

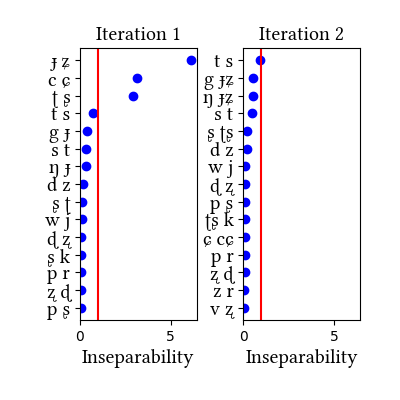

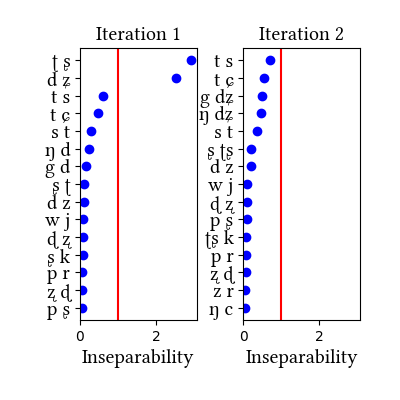

Polish also supplies an unusual argument in favor of an affricate analysis of [ʈʂ, ɖʐ], which famously contrast with stop-fricative sequences [tʂ, dʐ] (the fricatives in these are derived from historical rhotics; see the Brooks 1964 citation mentioned in the paper). The simulations we report below reflect this contrast in the transcriptions, because it is represented in the orthography. One corollary of the contrast is that the retroflex affricates have categorically inseparable first halves; there are no freely occurring retroflex stops otherwise. It is interesting, therefore, that our learner does not succeed in identifying [ɖʐ] in any of the simulations. This is because this affricate is a bit defective in the language's phonology--it occurs in loanwords and in morpho-phonological derived environments only, and it is overall rather rare (two orders of magnitude rarer than the voiceless counterpart). This shows that the "trick" of narrowly transcribing affricates, as in the English simulation, is not really a trick, since it does not always help the learner find the desired segments. Categorical inseparability is not the same as inseparability in our learner's calculations.

Typologically, the comparison between Russian and Polish is instructive: voiced affricates are typologically dispreferred (see Marzena Żygis's work on this), and in Polish, the typologically dispreferred voiced sequences are so type-rare that our learner has a difficult time unifying them.

Beyond affricates, one difference between Polish and Russian is that Russian has a clear and robust palatalization-velarization contrast in most of its consonants, whereas in Polish, the contrast is more difficult to analyze and is more controversial (see Gussmann 2007, Bethin 1992, and many others). In the Polex simulations, we transcribed all of the controversial sequences as clusters except for prepalatals, which can occur in word-final position (e.g.,

Simulation data at a glance

Click on simulation name to view additional simulation details.

| Simulation name | Initial state Learning Data | Initial state features |

|---|---|---|

| Polex Narrow | LearningData.txt | Features.txt |

| Polex Broad | LearningData.txt | Features.txt |

| Childes_Cds Narrow | LearningData.txt | Features.txt |

| Childes_Cds Broad | LearningData.txt | Features.txt |

Simulation details for Polish polex narrow

Input:

The data for this simulation come from POLEX (Vetulani 2000). All of the ~98,000 words are included. The transcription script for converting the POLEX ASCII pseudo-orthography into IPA is here. Voicing assimilation is transcribed in this simulation. The difference between the "narrow" and the "wide" transcriptions are in the representation of orthographic <ć, dź>: in the narrow transcription, they are transcribed as [cɕ, ɟʑ].

LearningData.txt | Features.txt

Summary of iterations:

| Iteration | Learning Data produced | Features produced | Inseparability | New Segments added | Segments removed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

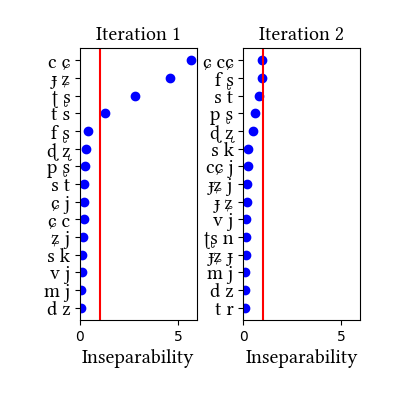

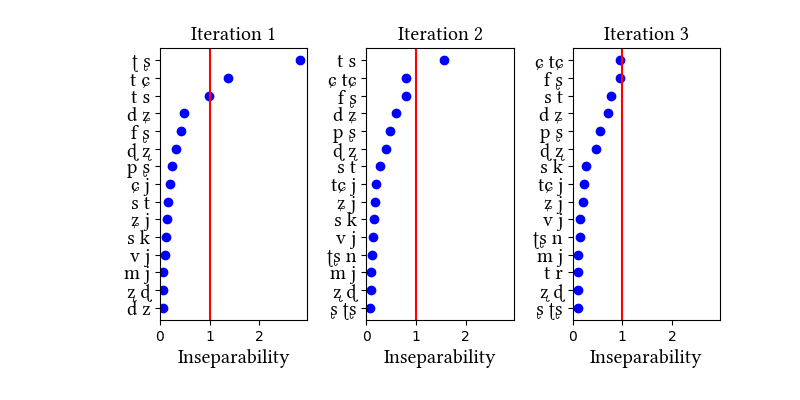

| 1 | LearningData.txt | Features.txt | [download] [view] | ts, ʈʂ, cɕ, ɟʑ | None |

| 2 | No new learning data | No new features | [download] [view] | None | None |